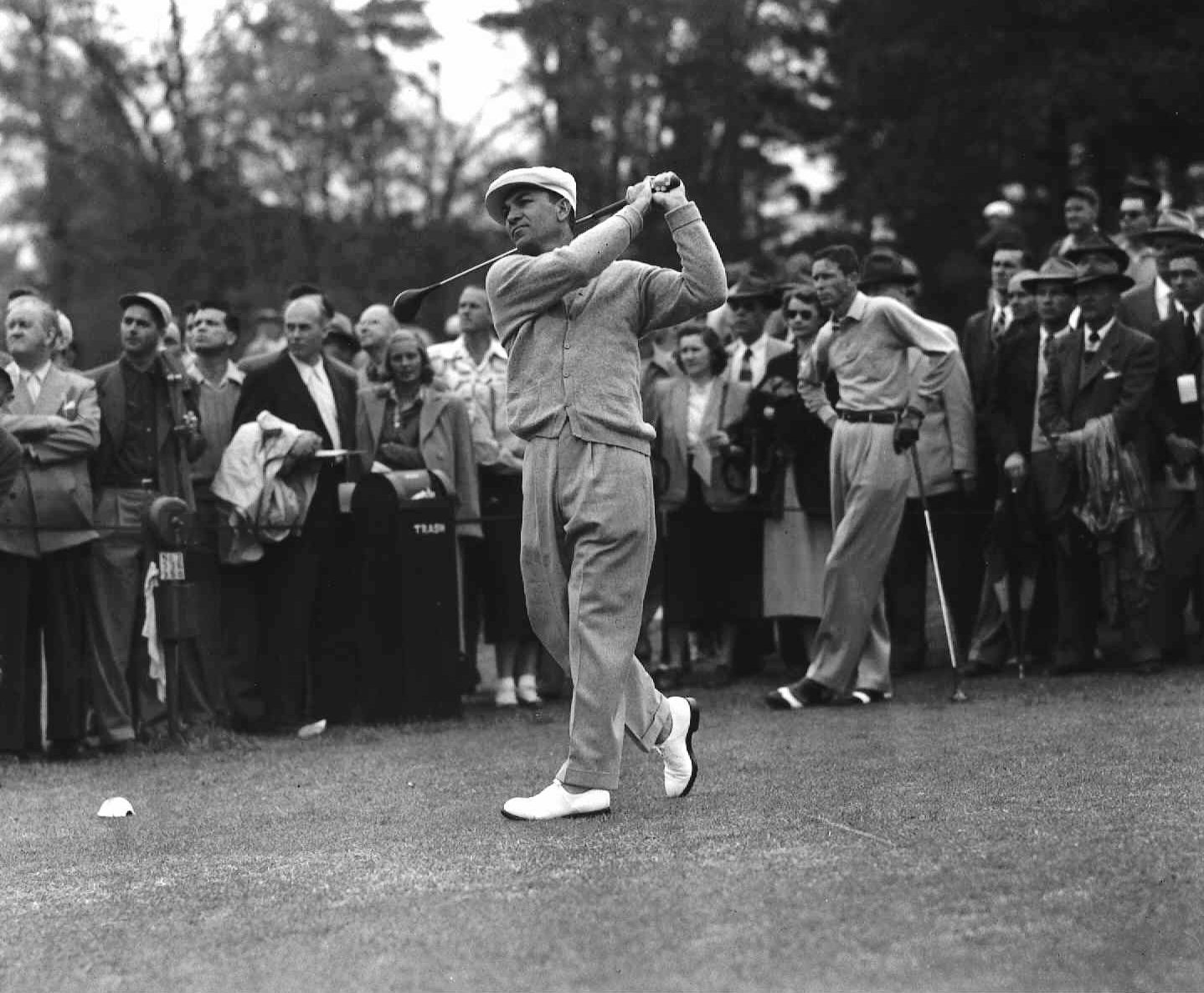

The parallels between the car crash that sent Tiger Woods to the hospital and the 1949 crash that sidelined Ben Hogan couldn’t be more clear.

At the time of their crashes, both Woods and Hogan were among the best to ever play professional golf. Both were lucky to be alive after the crashes, Hogan in a head-on collision with a bus on a foggy Texas highway in 1949 and Woods on a winding, downhill street in Rancho Palos Verdes just last month.

While Woods’ recovery and his future as a golfer are still in question, Hogan crafted one of the most remarkable recoveries and comebacks in sports history. He won six more major championships after the bus crash, including all three majors he played in 1953.

What many fans don’t know, even in the Coachella Valley, is that the desert played a large part in Hogan’s recovery. In an era when even top pros took winter jobs as head professionals at country clubs, Hogan became the head pro at a new club, Tamarisk Country Club in Rancho Mirage.

“He definitely still resonates with golfers once they know he is affiliated with the club,” said Chad Johnson, general manager at Tamarisk. “Believe it or not, there are a lot of people who don’t know or didn’t know until they came to the club.”

While none of the current members at Tamarisk were around in the 1950s, Johnson said the club does have members whose parents were at Tamarisk in the 1950s for Hogan’s short but celebrated time as the head pro. But one desert resident remembers Hogan as an important part of the early country club.

“They needed his name to sell lots,” said Shirley Spork, one of the original 13 founders of the LPGA and a teaching pro at Tamarisk starting in late 1953. Hogan was no longer the head pro when Spork started at the club, she said. Instead, the head pro was tennis star-turned-golf pro Ellsworth Vines.

With the new club from the start

According to Tamarisk’s official 50th anniversary book published in 2002, the idea of hiring Hogan came from Sidney Lanfield, a film director and a founding member of the club. Lanfield has directed “Follow the Sun,” the film about Hogan’s life, crash and recovery which came out in 1951 starring Glenn Ford.

Various reports say Hogan was offered a five-year deal for $95,000 plus another $25,000 to be put toward a home to spend a few months each winter in the desert. Other reports say Hogan was offered just $10,000 a year.

Whatever the offer, Hogan agreed and started with Tamarisk in 1952, the year the club opened. As much as the money, the appeal to Hogan of the Coachella Valley was as a burgeoning golf destination where he could practice and play through the winter months on legs that had been badly damaged in the crash and that were never truly close to 100 percent again.

How engaged was Hogan as an actual golf pro? As might be expected, not very, Spork said. Hogan’s reputation was of an icy golfer who rarely acknowledged his playing partners, and Spork said her time at Tamarisk was filled with stories of Hogan not engaging members very often for things such as lessons or running the pro shop.

“He wanted to work on his health and legs and so he came to Tamarisk,” she said. “You would be telling the truth there.”

But in a 2007 interview with The Desert Sun, Tamarisk member Dolores Hope, wife of famed comedian and golfer Bob Hope, said Hogan’s glower reputation wasn’t warranted.

“Ben was a very, very sweet man,” Hope said. “He had a nice sense of humor. He just looked like he had a machine gun in his golf bag when he was on the course.”

Spork remembers people telling her Hogan would practice in the morning, then come to his office and keep the door closed. Johnson said he’s talked to members who relate that Hogan was friendly in fact to members. But the purpose of being at the club was to work on his game and gain strength in his legs.

In 1950, the year after the crash, Hogan played nine events and even won the U.S. Open. But in 1951, Hogan played just four events, winning the Masters and the U.S. Open. In 1952, Hogan’s starts were down to three, though he won the Colonial Invitational in Fort Worth, Texas, placed third in the U.S. Open and seventh in the Masters.

Even in Hogan’s fabled year of 1953, when he won the Masters, the U.S. Open and the British Open – he had not played the PGA Championship and its match-play format since before his crash – Hogan played just eight tournaments. Hogan’s time in the desert was used to sharpen his ball-striking skills.

“He had Gardner Dickinson (who won seven PGA Tour events on his own) working for him. He would take (Dickinson) way out to the 15th, 16th hole,” Spork said. “He would practice and Gardner would shag balls for him.”

“He took advantage of playing,” Johnson said. “My understanding from some of the members was he did play a lot. And he was very friendly with the members.”

Hogan also worked on his putting, a weakness in his otherwise Hall of Fame game. He famously said Tamarisk had the best greens in the county.

By 1954, Hogan was no longer the head pro at Tamarisk, though he did play the course in February of 1954 with President Dwight Eisenhower, making his first trip to the desert. While the warm winter weather and the ability to play and practice in the desert helped Hogan continue his comeback from the crash, Hogan never won a major championship after 1953. He continued to play fewer than 10 tournaments a year, often fewer than five tournaments, through the rest of the 1950s and through 1967.

But Hogan, his comeback and his time in the desert remain legend at Tamarisk.

“His story is huge here,” Johnson said. “And we anticipate that history will continue to grow, because we are talking about using Ben Hogan’s name in some ways as we move forward.”

![]()