Have you ever had a read at some of the stuff cobbled together by the Global Odds Index?

It’s an organization that examines all sorts of probabilities in life, from winning the lottery or getting struck by lightning to the chances of you understanding what the Dickens I’m prattling on about in my column.

According to findings in the latest study by the Global whatstheirchops, the odds of a Brazilian male becoming a professional golfer are 1 in 7.7 million.

About the same, then, of a reader – yes, a reader like you with that increasingly glazed look – getting to the bottom of this ruddy page. So, let’s crack on. The odds are stacked against us. We’ll start with green-reading books.

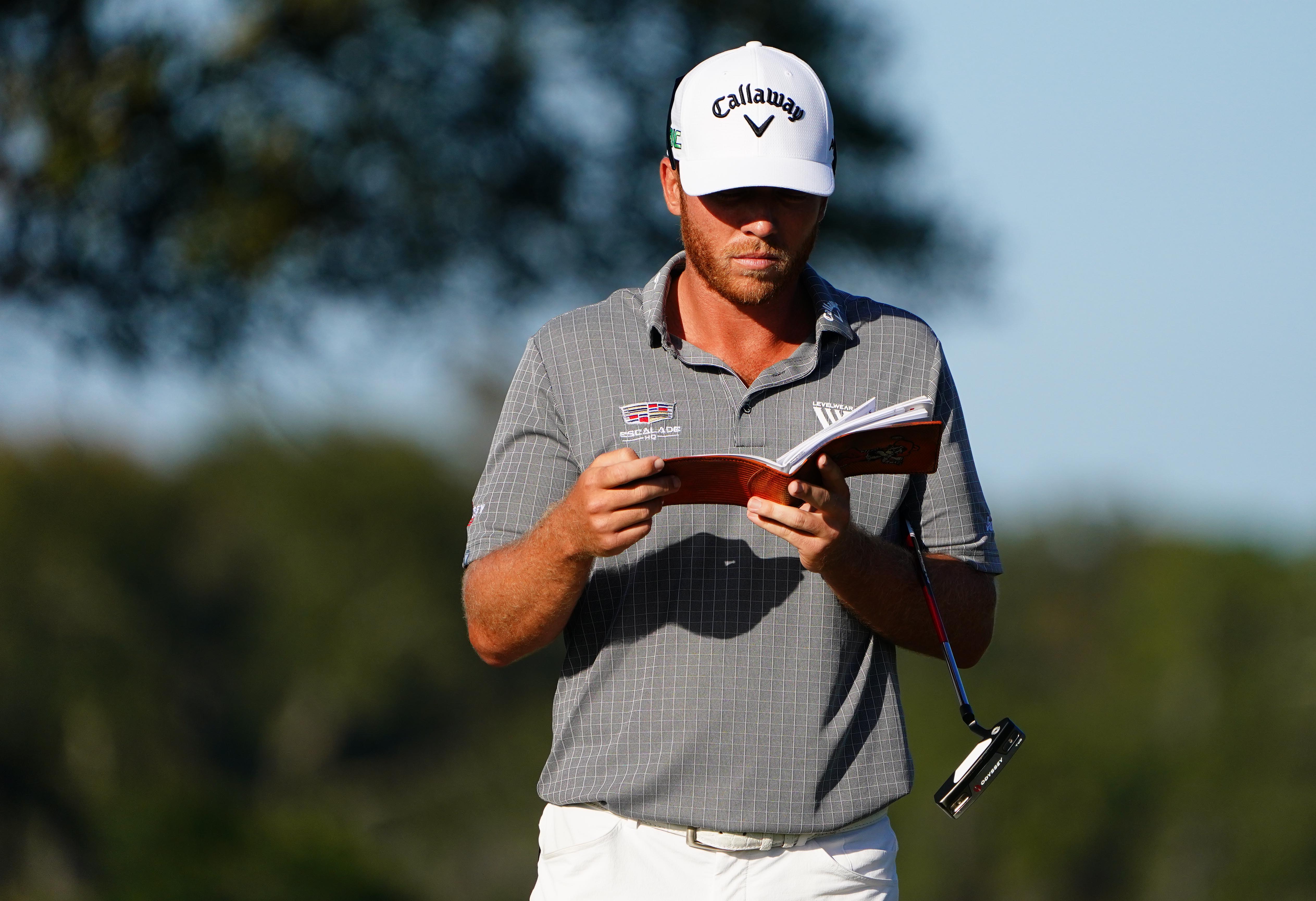

Watching certain modern-day professionals examining the line of a putt with one of those highly detailed compendiums is broadly equivalent to peering at someone scrutinizing a particularly intrepid diagram of techniques in the Kama Sutra.

They’ll study the myriad slopes, curves, and borrows of the putting surface while contorting themselves into various positions for a better view during an elaborate and tiresome process which often ends in the sighing, eye-rolling anti-climax of it being left woefully short. Now, there’s a colourful description of a tricky 15-footer that really should be read after the watershed.

Recently, golf’s governing bodies, the R&A and USGA, unveiled a Model Local Rule to further reduce the use of green-reading paraphernalia at the highest level of competitive golf.

The rule MLR G-11, which admittedly looks like a personalised number plate you’d see on a swanky car parked outside the R&A clubhouse, will, as of January 1 2022, enable a committee to establish an officially approved yardage book for a competition so that the diagrams of greens show only minimal detail.

In addition, the local rule limits the handwritten notes that players and caddies are allowed to add to the approved yardage book.

The purpose? “To ensure that players and caddies use only their eyes and feel to help them read the line of play on the putting green.”

Now there’s a novel idea.

Getting a small ball to disappear down a hole has been the bane of many a golfing life through the ages. The mighty Old Tom Morris, for instance, was so renowned for his putting woes, a letter sent back in the day simply addressed ‘The Misser of Short Putts, Prestwick’ was delivered straight to him by the postman.

And what was it Tony Lema once uttered about the putter? “Here is an instrument of torture, designed by Tantalus and forged in the devil’s own smithy.”

Putting has always been the ultimate test of nerve and skill. For those of us of a more old-fangled approach, watching golfers consulting some kind of Ordnance Survey map on the green while embroiled in an extravagant, time-consuming pre-putt routine that resembles the complex mating rituals of the Greater sage Grouse tends to grind the teeth.

In an age when craft, feel and instinct can be sacrificed on the altar of advancements in aids and accoutrements, players will always use something or other in an effort to gain an advantage if someone else is using the same something or other.

The more that’s available, the more they’ll add to the armoury. It’s in a golfer’s nature. On a slight detour from the topic, I remember nipping along one year to a World Hickory Open at Craigielaw along Scotland’s golf coast and some of the country’s up-and-coming pros and amateurs who were competing revelled in the opportunity of playing with just five clubs and no assistance from stroke savers, course guides or any other visual aids. The senses were roused and they relied on sheer golf intuition.

Amid the general clutter of thoughts and processes than can make this such a mind-mangling game, sometimes less is more.

As for these green books? “I use a green book, but I’d like to get rid of them,” admitted Rory McIlroy earlier in the season. “For the greater good of the game, I’d like to see them outlawed and for them not to be used anymore.”

McIlroy, and others, may get their wish.